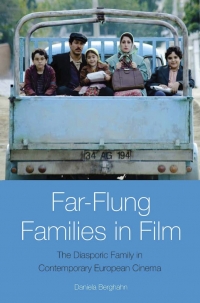

Far-Flung Families in Film published!

If you found some of the entries on this website interesting, you will be able to find out a great deal more about the subject by reading the book Far-Flung Families in Film: The Diasporic Family in Cinema, which was published earlier this month by Edinburgh University Press.

You can order the book at Amazon.co.uk or at Edinburgh University Press

In this monograph I seek to answer a number of key questions: Why have films with diasporic family narratives increased in popularity in recent years? How do representations of the diasporic family differ from those of more dominant social groups? How does diasporic cinema negotiate the conventions of film genres commonly associated with the representation of the family?

In the age of globalisation, diasporic and other types of transnational family are increasingly represented in films such as East is East, The Grand Tour (Le Grand Voyage), Almanya – Welcome to Germany (Almanya – Willkommen in Deutschland), Immigrant Memories (Mémoires d’immigrés: l’héritage maghrébin), Couscous (La graine et le mulet), When We Leave (Die Fremde), Monsoon Wedding and My Big Fat Greek Wedding. While there is a significant body of scholarship on the family in Hollywood cinema, this is the first book to analyse the representation of families with an immigration background from a comparative transnational perspective. It focuses on Europe’s most established transnational film cultures, Black and Asian British, Maghrebi French (or ‘beur’) and Turkish German cinema, and analyses key trends from the mid-1980s to the present.

Drawing on critical concepts from diaspora studies, cultural anthropology, socio-historical research on diasporic families and the burgeoning field of transnational film studies, this book offers original critical perspectives to scholars and students who are researching families and issues of race and ethnicity in cinema, the media and visual culture.

Reviews

'Far-Flung Families in Film explores the conflicted tensions sustaining its key terms "diasporic' and 'family'. Giving full scope to the centrifugal and centripetal forces at work, Daniela Berghahn admirably proves that the "transnational turn" has energized not only filmmakers, but invigorated debate among the academic community as well.' - Thomas Elsaesser, author of European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood

'Daniela Berghahn provides a timely, wide-ranging, and engaging analysis of diasporic family films made by key directors from around the world living in Europea and identifies a new European cinema in the new multicultural Europe.' - Hamid Naficy, author of An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking

'This beautifully illustrated book is a milestone in the study of diasporic film and 'accented cinema' (Hamid Naficy), and it also marks a particularly original and much-needed contribution to transnational cinema studies.' - Book review by Márta Minier in Transnational Cinemas, 5:1, 2014

Introduction

The introduction situates this study in the context of the two principal fields of enquiry with which it intersects, namely scholarship on the representation of the family in (predominantly Hollywood) cinema and the rapidly growing body of work on transnational cinema, more generally, and diasporic European cinema, in particular. The overarching argument of the book, which is outlined in the Introduction, is that the diasporic family on screen crystallises the emotionally ambivalent response to growing cultural diversity in Western societies. Constructed as Other on account of their ethnicity, language and religion, diasporic families are perceived as a threat to the social cohesion of Western host societies. At the same time, many diasporic family films reflect a nostalgic longing for the traditional family, imagined in terms of extended kinship ties and superior family values.

Chapter 1: Family Matters in Diaspora

The chapter examines and defines the book’s key concepts, ‘the family’ and ‘diaspora’, drawing on research in anthropology, sociology, migration and diaspora studies. A succinct social history of postwar immigration demonstrates that the shift from primary migration to family reunion in the 1970s facilitated the formation of diasporic families who settled in France, Britain and Germany. When the second generation that was born and/or raised in the host society came of age, it sought to gain control over their cultural representation. The biographies of some of Europe’s most prominent diasporic filmmakers and scriptwriters, including Gurinder Chadha, Hanif Kureishi, Ayub Khan-Din, Mehdi Charef, Abdellatif Kechiche and Fatih Akın – all members of the second generation – suggests that without family reunion the kind of diasporic film culture that emerged in British, French and German cinema almost simultaneously from the mid-1980s onwards would never have come into existence. From the mid-1990s onwards, a growing number of films about families were made. The narrative construction of these families resonates with personal as well as political agendas. The intertwining of the familial and the national indicates that the diasporic family functions as a trope of postnational belonging.

Chapter 2: Families in Motion

Invoking Bakhtin’s influential concept of the chronotope and its productive appropriation in Paul Gilroy’s discussion of the Black Atlantic and in Hamid Naficy’s work on accented cinema, this chapter focuses on families in motion. Its overriding concern is how transnational mobility affects the structure of the family and its identity. Many films chart journeys of outbound and homebound migration, whereby home does not necessarily signify the place of origin buy may designate a spiritual home, such as Mecca is home for the global Muslim community. Home-seeking journeys often lead to disillusionment or death, thereby challenging the myth of a glorious homecoming, regarded by many scholars as fundamental to the diaspora experience. The chapter’s second line of enquiry probes the films’ generic and stylistic strategies and asks how Journey of Hope (Reise der Hoffnung), The Edge of Heaven (Auf der anderen Seite), Almanya – Welcome to Germany (Almanya – Willkommen in Deutschland) and The Grand Tour (Le Grand Voyage) inflect and modify the conventions of the road movie.

Chapter 3: Family Memories, Family Secrets

Whereas memories are the family’s public face, secrets are its dark underbelly, the shameful events that have been ruthlessly edited out. The first part of this chapter uses Pierre Nora, Marianne Hirsch and Alison Landsberg’s writings on memory at its critical framework. It analyses postmemory documentaries, including Immigrant Memories (Mémoires d’immigrés: l’héritage maghrébin) and I For India in which diasporic filmmakers excavate their parents’ memories of migration. These documentaries, which make extensive use of family photos and archival footage, triangulate the memory and postmemory within the family, the collective memory of diaspora and official accounts of immigration, preserved by the host societies.

The second part explores the phantoms that haunt families, such as illegitimate birth and uncertain parentage, focusing on the most prevalent secret and its revelation: the ‘coming out’ of queer sons and daughters in the diasporic family. The queer diasporic identities at the narrative centre of Lola and Bilidikid, My Beautiful Laundrette and Nina’s Heavenly Delights function as a master trope of hybridity and critique fantasies of purity, which simultaneously underpin the ‘natural family’ based on bloodline, heteronormativity and supposedly natural gender hierarchies, and nationalist ideologies, based on ethnic absolutism and other homogenising concepts.

Chapter 4: Gender, Generation and the Production of Locality in the Diasporic Family

This chapter examines the dynamics of gender and generation in the diasporic family, broaching contested issues such as wearing hijab and honour killings in relation to (Muslim) patriarchy. Arjun Appadurai’s concept of the production of locality and Laura Marks’s theory of embodiment in intercultural cinema of the senses provide pertinent critical frameworks. In many diasporic family films, the production of locality is imagined as the cause of gender and generational conflict. Through adhering to the traditions, language and rituals from the homeland, parents profess their allegiances to a place and community far away. Their Westernised offspring, by contrast, typically engage in the production of culturally hybrid localities in the streets and playground of urban youth culture and on their bodies. Close readings of When We Leave (Die Fremde), East is East, West is West and Couscous (La graine et le mulet) attend to the consumption of media and food and the performance of gendered and generational topographies.

Chapter 5: Romance and Weddings in Diaspora

Why do weddings proliferate in diasporic family films and what it is about the big fat diasporic wedding that captures the imagination of diverse audiences? After providing a succinct survey of the wedding theme in its many variations, ranging from films about arranged marriage, sham weddings and interethnic romance, the chapter explores diasporic wedding films in terms of their generic characteristics. Wedding films emerged during the 1990s as an identifiable strand of the romantic comedy in mainstream cinema in the West and, as a variation of the romantic family drama, in Bollywood. Four Weddings and a Funeral and Hum Aapke Hain Koun (Can You Name Our Relationship?) are widely cited as the foundational texts, while My Big Fat Greek Wedding established the generic paradigm of the diasporic wedding film. The overriding concern of this chapter is how Evet, I Do!, (Evet, ich will!), Monsoon Wedding and Bride and Prejudice hybridise the genres of melodrama, romantic comedy and the wedding film through a distinctive diasporic aesthetics.

Edited on 12 Sep 2014 around 9am

Category: Films